The Machinations of a Monster

May 19, 2022

We all know what monsters are. They’re big animals with huge horns, long fangs, and sharp claws. They attack everything on-sight and can only be brought down by the strength of a hero in shining armor.

…Right?

Such thoughts are, of course, some of the first to arise when the term ‘monster’ is thrown around. But, perhaps just as often, we think of some people who are particularly evil – so evil, in fact, that we equate them to oftentimes over-exaggerated myths that are capable of leveling entire cities.

So… what is a monster, exactly?

At a glance, the easiest ‘definition’ (if you could call it that) which encompasses both mythical and human monsters would claim that monsters are incarnations of evil. Violence. Destruction. In other words, monsters are… the bad guys, or something like that. I mean, it’s obvious, isn’t it? You and I are the heroes, and our enemies are the monsters we need to defeat in order to save the world.

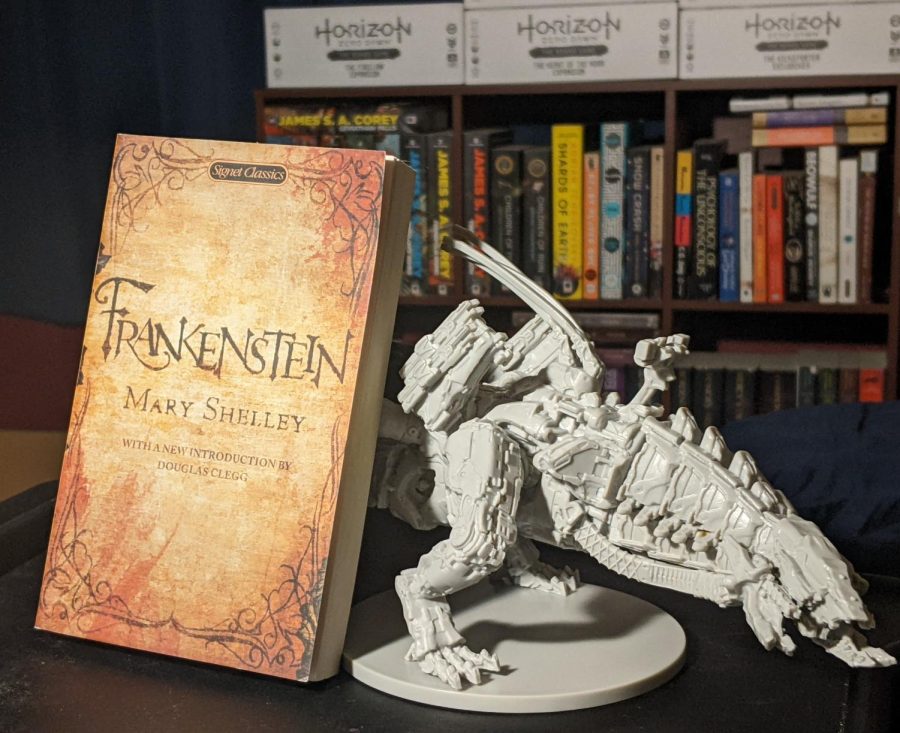

Such a definition begins to fall apart, however, when we consider the renaissance that came to life in 1818 with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus. In Frankenstein, we’re given two potential monsters: Victor Frankenstein and his creation. The creator could be considered a monster of sorts for several reasons, many of which revolve around his creation of and his relationship with his creature. His monster, meanwhile, commits many of its own atrocities.

With these two potential monsters, we come back to the need for a distinction between a grotesque creature and a human with distorted intentions. Frankenstein’s monster fits the bill physically, but not quite so much in terms of mentality. Victor himself is something of a mad scientist, and his intention to create life but not care for it makes him a more psychological monster.

There are two things we can glean from these monsters. The first is another definition: a monster is something that is utterly unnatural. Neither Victor nor the creature are inherently monsters; rather, their existences and actions go against the natural order of the world, which is what makes them into monsters. The second gleaning is… something of a rabbit hole.

Think back to a story that you’ve recently watched or read. In that story, can you think of any character who fits the description of a monster, in one way or another? Chances are, you can. The antagonist is usually the first one who comes to mind, but then you think a little bit more, and…

Wait. Is the protagonist a monster, too?

Now, I’m willing to concede that such thoughts won’t easily fit into every story or piece of media in recent times. But, if you think about it, more and more stories in the modern day depict a wide range of characters – be they the good guys or the bad guys or someone in between – as monsters. These depictions are, most likely, a satirical commentary on how we as a society have always thought about monsters. If what my English teachers say is anything to go by, if satirical commentary exists, the original argument surely has a flaw of some kind that needs to be addressed.

In this case, that flaw is almost certainly the idea that a monster has to be strictly evil, violent, unnatural, et cetera. Sure, the word “monster” is used to indicate something that is evil or unnatural, but a monster, a genuine creature in most cases, does not have to inherit its namesake. In fact, plenty of those modern day satirical commentaries have the overarching theme of “Humans were the real monsters all along!” The supposed monsters, usually creatures or people who are different or “unnatural,” are usually not to blame in these cases – not entirely, at least.

Thus, a strangely familiar thought comes to mind:

“When is a human a monster, and when is a monster human?”